The American Chestnut

To speak of the American chestnut tree is to speak of a tragedy. Like many, I only knew of the chestnuts, which come from the tree itself. I first learned of them as a child hearing Nat King Cole’s 1946 “The Christmas Song” where he talks of “chestnuts roasting on an open fire”. It’s a comforting image, though not one many of us can visualize, for it hails to a time none of us would’ve remembered. By 1946, the American chestnut tree was all but decimated, its fruits no longer available for roasting or otherwise.

Since then, chestnuts have dimmed considerably in our memories. Most of us know of them, but rarely do we have the chance to see fresh chestnuts, or enjoy the taste of a once beloved fruit (despite the hard outer shell and ‘nut’ being in the name, chestnuts are in fact fruits). The ones that are available in American supermarkets now come from China, Korea, or Italy, from trees that are just slightly different from the American chestnut.

How is it that something once so prominent can disappear so quickly? How is it we’ve forgotten something that once held such value in our culture?

The unmaking of a tree

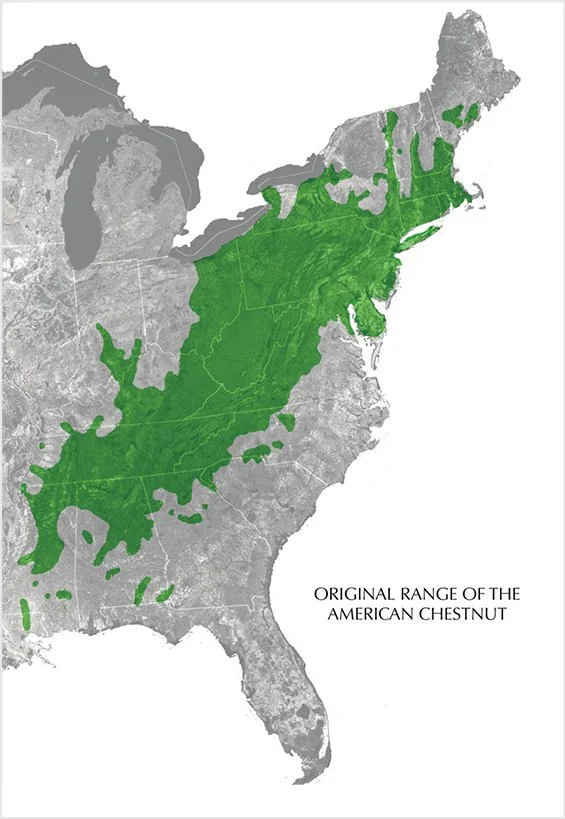

Map of the range of the American Chestnut. Image from Hudson Valley Table.

For centuries, perhaps even millenia, the American chestnut tree could be seen all along the Eastern seaboard. They were particularly common along the Appalachian mountain range, tall and wide (some reaching up to 100 feet in height and 13 feet in width).

This fact alone astounded me; I’ve lived the majority of my life on the east coast, and grew up with the Appalachian mountains in my backyard. Unbeknownst to me at the time, the woods that surrounded my house might’ve looked remarkably different only a few decades before my parents arrived in the early ‘90’s.

They were everywhere, as important for the native wildlife as it was for the Native Americans who prospered from its fruits. Later European settlers were first more interested in the wood. Chestnut wood was impervious to rot, which made it useful for all manner of constructions: houses, fences, cradles, coffins, storage boxes, etc. Over time however, they too managed to thrive off the chestnut fruits, using them for food and in exchange for other goods.

An example of a canker on a young chestnut tree. Image from Norfolk Trees.

In 1904, an Asian variety of chestnut tree came to America, and unbeknownst to those that brought it, it was impregnated with a fungus known as cryphonectria parasitica. The result was nothing short of devastating, and what plant biologists describe as a prime example of an ecological disaster. Once a tree was infected, it took less than three years for it to completely perish, its trunk riddled with cankers.

What was worse, the fungus spread far and speedily, spreading approximately 50 miles per year. Within 40 to 50 years after the arrival of the fungus, the majority of America’s chestnut trees were long gone. It’s estimated that 3 to possibly 4 billion chestnut trees died, enough to drastically change the landscape and a way of life for those that had lived and prospered from the tree for centuries.

The chestnut tree in Appalachia

Giant American chestnut trees in the Smoky Mountains, c. 1910. Image from The Dark Mountain Project.

Because chestnut trees produced edible fruits, and because the chestnut tree could be seen practically everywhere in Appalachia, its destruction brought down an entire way of life not only for the people who’d settled in the region, but its native wildlife.

Several animal species, bears, squirrels, turkeys, relied heavily on the food of the chestnut tree. Without this previously reliable source of food, and little else to replace it with, several species starved or simply moved away from the region to one with a more plentiful supply of food. Several native insects that relied solely on the chestnut tree either perished (it’s estimated that seven species of moth became extinct due to the blight) or moved to other regions.

This meant also that the people of Appalachia were suddenly faced with a dwindling amount of food. Where once they could hunt a robust squirrel, they now found only half-starved creatures. Being used to expecting up to ten bushelfuls of chestnuts from one tree, which could be eaten, given to livestock, or ground into flour, they now had nothing with which to feed themselves, their livestock, or use for bartering.

With the destruction of the chestnut tree then, their entire way of life disappeared. Farmers now had no choice but to find work outside the farmstead, leaving behind their lifestyles of self-sufficiency and learning to live off wages, canned goods, and highly processed foods.

Gone but not forgotten

Image of chestnut fruits, from Hudson Valley Table.

Seeing packages of pre-shelled, prepared chestnuts in an unremarkable package somewhere in the middle of a grocery aisle, I feel saddened by just how quickly something so beloved and important has disappeared from our culture. What is still a celebrated fruit in other parts of the world (Barcelona has Castanyeda festival every autumn) is practically unknown and uncherished in America.

But there’s reason to hope. Despite the devastation of the American chestnut, it still lives, even if only in dwindling numbers. The virus that so decimated the tree population is one that can’t thrive in soil, meaning chestnut tree sprouts have been known to grow and thrive briefly in sunny locations, only to later succumb to the blight. While this essentially means that the tree is ‘functionally extinct’, organizations like the American Chestnut Foundation are doing everything they can to change this.

Stump of a chesnut tree with sprouts growing. Image from Edge of the Wood Nursery.

Plant biologists have been working for years to grow a tree that is resistant to this blight. With some genetic modifications, some of these experiments have created trees that reach maturity. And with any luck, soon they’ll be able to populate, create large forests like the ones of old, producing vast numbers of American chestnuts, like the ones of old.

While it would take decades, even centuries for the chestnut tree to fully repopulate in its former native region (long before I have a chance to see it), there is something marvelous about its potential resurgence, like the past coming back to teach us about how marvelous trees of the past were and how they can be marvelous still, if only we remember to care about them.